Stemmata

The Syriac Tradition

Author: Simon Birol

I. Neo-aramaic text witnesses

The story of Ahiqar is transmitted in Classical Syriac as well as in the Neo-Aramaic dialects of the West and East Syriacs (also known as 'Assyrians', 'Chaldeans' or 'Arameans'). The Neo-Aramaic versions seems to be translated from the Arabic language and thus, they have been put aside for the Syriac branch. Ordered by creation date, these are the text witnesses:

A. Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin, Sachau 339 (listed in Sachau's catalogue as limit identifier 290)

- Pages: 117 (fol. 1r-59r)

- Date of creation: 1881-1889

- Copyist: 'Ešaʻyā of Qilith

- Provenance: West Syriac (dialect of Tur 'Abdin)

- Catalogue entry: Sachau 1889, 2:815

- Link to the digitized original: https://digital.staatsbibliothek-berlin.de/werkansicht?PPN=PPN862951585&PHYSID=PHYS_0005 (opens new window)

- Transcription & translation: Lidzbarski 1896

B. British Library (London), Brit. Libr. Add. 9321 (also known as "MS London-Sachau 9321")

- Pages: 167 (fol. 536b-620b)

- Date of creation: ca. 1897

- Copyist: Ǧibra'īl Qūryaqūzā

- Provenance: East Syriac (dialect of Alqosh (Iraq))

- Catalogue entry: not available

- Link to the digitized original: not available

- Transcription & translation: Braida 2014

C. Tellkepe (Iraq), QACCT 135

- Pages: 31 (fol. 230a-246a)

- Date of creation: 1937

- Copyist: Deacon Matīkā bar Yawsep mār Mīkā bar Qūryaqūs bar Ǧerǧīs Ḥadādē beth Ḥaǧī

- Provenance: East Syriac (dialect of Alqosh (Iraq))

- Catalogue entry: https://w3id.org/vhmml/readingRoom/view/136599 (opens new window)

- link to the digitized original: https://w3id.org/vhmml/readingRoom/view/136599 (opens new window)

- Transcription & translation: not available

Furthermore, there is the oral testimony from Mlaḥsō (South East Turkey) that has been taken from an Arabic version and will be excluded, too (cf. Talay 2002).

II. Text witnesses in Classical Syriac

For the text witnesses in Classical Syriac, the situation is quite different: All in all, there have been identified 22 manuscripts that can be divided into an East and West Syriac branch. Five of those manuscripts are lost and could not to be found. In one case, there are available readings of a lost manuscript as marginal notes of Harvard syr. 80 (= Ms. Urmia 270), while its submission (= Ms. Urmia 117) count to these lost text witnesses, too. Moreover, another lost manuscript (= Ms. Graffin) has been transcribed prior to its lost by Nau.

Among the manuscripts from Tur Abdin is a copy of a published version. Therefore, this manuscript (= Midyat Mar Gabriel MGMT 192) will be neglected for this project.

II.I Lost text witnesses

A. College of Urmia (Iran), Ms. Urmia 115

- Pages: unknown

- Date of creation: 1868/9

- Copyist: Anonymous

- Provenance: East Syriac

- Catalogue entry: Sarau/Shedd 1898, 21

- Link to the digitized copy: not available

- Transcription & translation: not available

B. College of Urmia (Iran), Ms. Urmia 117

- Pages: unknown

- Date of creation: 1887

- Copyist: Šmū'īl Tḥūmānāyā d-Mazrʻā

- Provenance: East Syriac

- Catalogue entry: Sarau/Shedd 1898, 21

- Link to the digitized copy: not not available

- Transcription & translation: Readings are available in Harvard syr. 80;

- Further remarks: it is an uncompleted copy of a nearly 800 years old lost transmission

C. College of Urmia (Iran), Ms. Urmia 230

- Pages: unknown

- Date of creation: 1894

- Copyist: Yōḥanān bar Ṭalyā da-Tḥūmā

- Provenance: East Syriac

- Catalogue entry: Sarau/Shedd 1898, 37

- Link to the digitized copy: not available

- Transcription & translation: not available

D. College of Urmia (Iran), Ms. Urmia 270

- Pages: unknown

- Date of creation: probably 1898

- Copyist: unknown

- Provenance: East Syriac

- Catalogue entry: not available

- Link to the digitized copy: not available

- Transcription & translation: not available

E. Ms. Graffin

- Pages: 56

- Date of creation: 1908

- Copyist: Priest Elias (abbot of the monastery Rabban Hormizd and nephew of Bishop Addai Scher)

- Provenance: East Syriac ('Alqōš (Iraq))

- Catalogue entry: not available (cf. transcription & translation)

- Link to the digitized copy: not available

- Transcription & translation: Nau 1918-1919, 274-307 and 356-380

- Further remarks: Commissioned work for Bishop Addai Scher

II.II Copy of Dolabani's edition

Midyat (Tur Abdin), MGMT 192

- Pages: 39 (p. 3-42)

- Date of creation: 1964/5

- Copyist: Ḥanna Qermez

- Provenance: West Syriac (Tur Abdin)

- Catalogue entry: https://w3id.org/vhmml/readingRoom/view/123101 (opens new window)

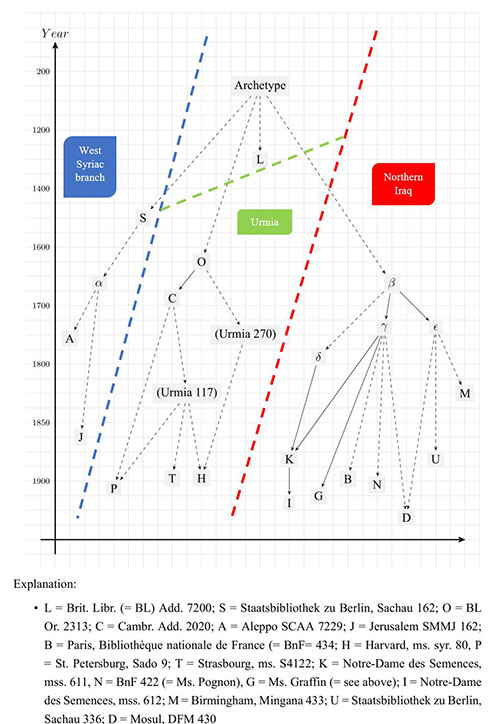

II.III Further text witnesses

The remaining 16 text witnesses (plus the copy of Ms. Graffin) can be displayed in this way: In the left, the West Syriac branch can be seen. Its oldest text witnesses dates from the 15th century. This manuscript is heavily damaged and has been torn within the sayings. The other witnesses transmit solely the sayings. However, Aleppo SCAA 7/229 contains even the parables. This manageable amount gives a clue why Bishop Dolabani (1885-1969) - one of the best experts of Syriac manuscripts of his time - published and corrected the first edition of Conybeare et al.: There were no available text witnesses in West Syriac circles at hand.

Another point is apparent: Several sayings from Aleppo SCAA 7/229 and Sachau 162 can be found besides the manuscripts, which were exclusively re-translated from a partly Arabic source (cf. Sayings). Therefore, it is possible that these West Syriac Manuscripts stem from a contaminated submission which contains parts from the Arabic re-translated sayings.

The remaining text witnesses belong to the East Syriac tradition. Apart from the two oldest fragment Brit. Libr. Add. 7200 and Brit. Libr. Or. 2313, the other manuscripts can be located precisely: One branch originates from Urmia (Iran) and was present until the beginning of WWI. Its most important text witness is Cambridge Add. 2020 and has been used as basis for the editions of Conybeare et al. Moreover, the submission ('Vorlage') of this manuscript has been identified as BL Or. 2313, because of its nearly entire accordance to it (cf. Proverbs).

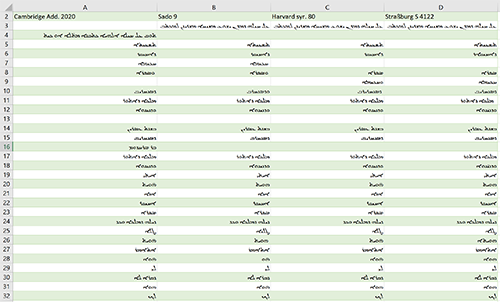

Though Cambridge Add. 2020 was written in Northern Iraq, it is quite different from other manuscripts of this branch (all of them were written in a later time). Furthermore, it has explicit affinities to the later manuscripts from Urmia, see e.g. the beginning of the text (in the same line (unless they are red marked) are identical words placed):

These three manuscripts are closely related to each other. This can be seen at best by a lost text passage in all three manuscripts, while Harvard 80 recompenses the lost text by using another submission (Ms. Urmia 117). However, the arrangement of the sayings and proverbs reveal that the copyist of Harvard 80 sticks to the same pattern (= Ms. Urmia 270) as Strasbourg S4122. Interestingly, Sado 9 can be described as a contaminated manuscript that follows mostly its submission Ms. Urmia 270 and partly uses another text. This can be seen by the arrangement of the sayings: The first 44 sayings are identical to Cambridge Add. 2020, so that its other submission has to be in close relationship to this manuscript.

A second East Syriac branch is rooted in Northern Iraq. This branch has additions and annotations that were missing in the Urmia tradition. Furthermore, this tradition can be divided into two branches: The red marked branch consists of two manuscripts that have been mostly reconstructed from defective manuscripts (some parts were even re-translated from an Arabic source). The older manuscript Birmingham Mingana syr. 433 is closer to the other manuscripts than Berlin Sachau 336 in regard of wording and word order. Only in Mingana syr. 433, the name of Ahiqar's son is transcribed as „Nadab“ (in accordance with Tobit 14:10) and not as „Nadan". Even in the Arabic tradition, this writing form is not attested, and a possible confusion of letters resp. points can be excluded. The proximity to Berlin Sachau 336 is obvious though Berlin Sachau 336 has several aberrations and additions (among others the highest number of sayings and parables). Thus, Nöldeke (1913, 54) is right by saying:

B (= Sachau 336; Anm. SB) ist also zusammengesetzt aus ziemlich arg entstellten Originalstücken und aus solchen, die aus dem Arabischen nicht sehr geschickt retrovertiert sind. Das wird so zu erklären sein: ein Abschreiber kopierte eine von vorn und gegen das Ende defekte syrische Handschrift und ergänzte sie durch Rückübersetzung aus einer arabischen. Dieser buntscheckige Text mag weiter durch verschiedene Schreiberhände gegangen sein und noch allerlei Ungemach erlitten haben, bis er die Gestalt gewann, in der er uns in der Sachauschen Handschrift vorliegt. Will jemand diese Gestalt ein Monstrum horrendum informe nennen, so kann ich ihm nicht widersprechen. Aber trotzdem kann die Wissenschaft auch aus diesem Achikar-Text Nutzen ziehen.

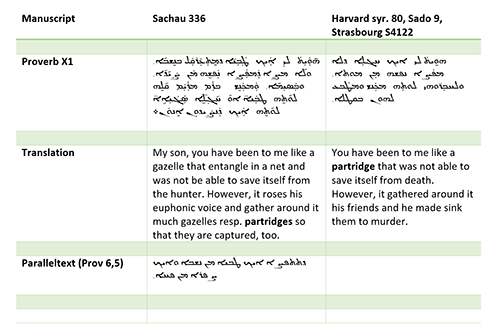

Further differences to other textual witnesses are related to the copyist's intervention, see e.g.:

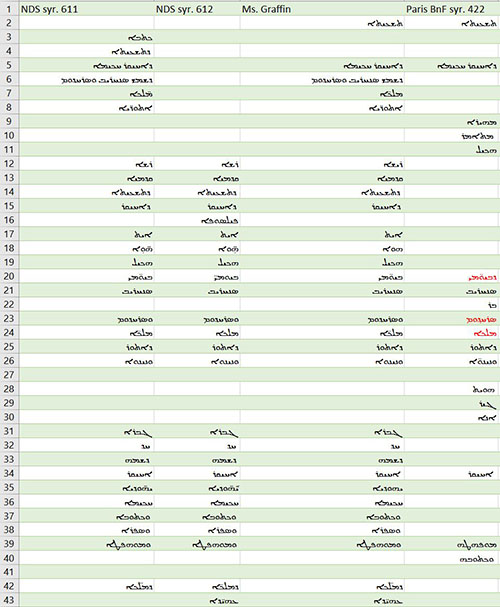

Mosul DFM 430 shows obvious connections two both text traditions of Northern Iraq. Futhermore, it contains several paraphrases and additions; some of them are solely transmitted in the Arabic tradition (e.g. the sayings D3 and D4 correspond to the sayings 89 and 90 of the Karshuni manuscript BL Add. 7209 cf. Sayings and Arabic Translation). Thus, it cannot been excluded that the copyist used beside its re-translated transmission a further Arabic textual witness for implementing these additions. The other four manuscripts from northern Iraq stand in a close relationship. At first, this applies to the manuscripts Notre-Dame des Semences, ms. syr. 611 and 612 (= NDS syr. 611 and 612) which transmitted readings of another manuscript as marginal notes. The last-mentioned manuscript is a copy of NDS 611. Ms. Graffin does not make mention of marginal notes, however, the order of word, sayings and proverbs reveals that this manuscript and NDS 611 stems from the same submission. The diferences of these manuscript to Paris BnF syr. 422 are minor:

Moreover, a scribe's remark at the end of NDS 611 is of particular importance: One of the submissions of this manuscript was an Arabic text of Ahiqar (cf. Manuscripts). Thus, the influence of the Arabic version on this textual witness is well proven. Regarding its close affinities to Ms. Graffin and Paris BnF syr. 422, the whole Northern Iraq branch of the Syriac version of the story of Ahiqar bears noticeable traces of its Arabic versions (esp. to the Arabic tradition C). All in all, the stemma can be constructed in this way:

How to Cite This Section

Birol, Simon. „Stemmata. The Syriac Tradition“. Ahiqar. The Story of Ahiqar in Its Syriac and Arabic Tradition, [Date]], ahikar.sub.uni-goettingen.de/website/stemmata.html.

The Arabic Tradition

Author: Dr. Aly Elrefaei

The Arabic and Karshuni’s manuscripts may be divided into four traditions (A, B, C, D) based on significant errors, additions and omissions, analogies and variances. The first and oldest tradition contains three witnesses (two Arabic and one Karshuni) dating from the 12th to 14th century. Only one Arabic witness from the 15th century exists for the second tradition. Seven witnesses (three karshuni and four Arabic) testify to the third tradition, which dates from the 16th to the 18th centuries. Twelve witnesses (four karshuni, eight Arabic) from the 18th and 19th centuries make up the fourth and greatest tradition.

Tradition A

Textual witnesses: Sbath 25, Vat. syr. 424, Vat. syr. 199

Tradition B

Textual witnesses: Vat. ar. 74

Tradition C

Textual witnesses: Brit. Add. 7209, Vat. syr. 159, Ming. syr. 258, Cod. Arab. 236, DFM 614, Sach. 339, Brit. Or. 9321

Tradition D

Textual witnesses: Paris. ar. 3637, Paris. ar. 3656, Cam. Add. 2886, Ming. ar. 93, Ming. syr. 133, Vat. ar. 2054, GCAA 486, Salhani, Borg. ar. 201, Leiden Or. 1292, Gotha 2652, Cam. Add. 3497

How to Cite This Section

Elrefaei, Aly. „Stemmata. The Arabic Tradition“. Ahiqar. The Story of Ahiqar in Its Syriac and Arabic Tradition, [Date], ahikar.sub.uni-goettingen.de/website/stemmata.html.